When the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic hit the world in March 2020, panic swept through stock markets everywhere including India, and share prices tumbled across the board. However, the story since then has been quite different, as stock markets quickly went on to recoup their losses and post handsome gains thereafter. In India, the Nifty 50 has doubled from its March 2020 lows, driven both by foreign investors who put in $14 billion in FY 2021 and domestic inflows amounting to about $25 billion in the same period.

The sheer strength of the bull market coming so soon after the despair of the pandemic has attracted millions of new investors into India’s stock market. According to the Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI), over 14 million new investors have entered the stock market in recent months. Before March 2020, there were around 11 million active investors in India. Since then, the number has more than doubled to around 25 million active investors. In September 2021, active demat accounts in India crossed the seven-crore landmark, highlighting the growing influence of retail investors in Indian equities. In fact, retail investors now command about 70 per cent of the market share in the average daily turnover while the turnover of institutions - including foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) and domestic institutional investors (DIIs) - declined to 30 per cent from 59 per cent in March last year. Go further back and as late as May 2015, this share was as high as 89 per cent.

Clearly, the rise of discount brokers like Zerodha, Upstox, Groww etc. have expanded the base of retail investors, as they have gained wide acceptance among the public with easier accessibility and lower costs. In comparison to traditional brokers and banks, they have succeeded in broadening the market base by tapping into people who either did not invest in stock markets or who did so only indirectly, for instance, through pension schemes. Their key selling point - low or no brokerage charges - has attracted many first-time investors from the smaller, less well-connected cities and towns, and their market share has increased from 26 to 44 per cent in the past year. Further, to extend their reach into the hinterlands, they offer their services in the regional languages as well. With discount brokers, ordinary investors have gained the confidence to invest small amounts in the stock market without fearing that their trading profits would be consumed by brokerage fees, as would happen with a traditional broker.

Remarkably, the trend of the increasing importance of retail investors seen in India has an exact parallel in the US too. The lockdowns and the work-from-home concept that took hold served as a catalyst for many Americans who now began to think about investing in the stock market. As with India and discount brokerages like Zerodha, the US also saw the rise of a trading app called Robinhood which altered the rules of the game. Prior to Robinhood, anyone who wanted to invest in stocks was charged between $5 to $10 a trade. They were also required to invest a minimum of $500 to open a trading account. That changed when Robinhood disrupted the market with its zero-commission trading, smart and user-friendly interface, hassle-free account opening process, and making it possible to invest in fractional shares.

According to informed estimates, retail investors accounted for 23 per cent of all US equity trading in 2021 which is more than twice the level of 2019. That suggests that their stock market presence is roughly as big as all hedge funds and mutual funds combined and behind only the high-frequency traders. A Deutsche Bank survey found that almost half of US retail investors were completely new to the markets in the past year. They are young (mostly under 34) and they are aggressive, as seen in their greater willingness to borrow money to fund their bets, to make heavy use of options to make bets on stocks, and to use social media as a research tool to gain trading insights.

What explains the rise of retail investors?

An important factor in the rise of retail investors is that lockdowns and the work from home lifestyle gave people extra time to explore the stock markets. They were then nudged into actual trading thanks to online discount brokerages like Zerodha in India and Robinhood in the US. Further, India has seen a dramatic rise in its 4g network coverage and data consumption. The exponential growth in smartphone usage has allowed Indians to access all kinds of financial services efficiently and without hassles. As of March 2021, India had the second largest number of internet users in the world with almost 825 million people actively using the internet each month. The Ericsson Mobility Report 2021 puts the total number of smartphone subscriptions in India at 810 million in 2020, accounting for 72 per cent of total mobile phone users in the country last year.

However, when it comes to altering the behaviour of millions of disconnected individuals and that too in such a short period of time, we need more than the existence of enabling factors. We need something that sets off a spark and lights the fire. Around the time the world went into lockdown mode in March/ April of 2020, share prices had collapsed dramatically and shares of many good companies were available at compelling valuations. Many retail investors who first entered the market in that period would have made handsome gains subsequently, thereby increasing their own appetite for more and also serving as successful examples to others, and draw in more investors.

Further, in the US, generous welfare payments were handed out by the Federal and state governments to their citizens which meant that many people had money in their bank accounts, but without avenues for spending the same given the lockdowns and travel restrictions. Trading in the stock market became an alternative channel to deploy some of this money. Besides, it goes without saying that one’s risk appetite is always greater when trading with money that comes into hand as an unexpected bonus, as compared to money that is earned by the sweat of the brow.

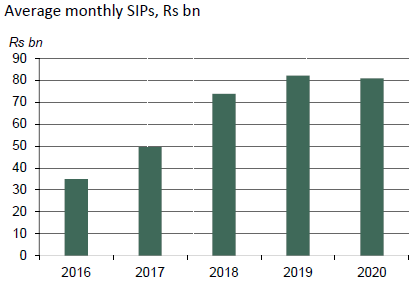

Back in India, interest rates on bank deposits were reduced along with lending rates as part of the measures to deal with the economic fallout of the pandemic. With low returns on conventional bank deposits, investors have been looking out for alternative channels to deploy their savings in search of higher returns. Also, the process of financialization of savings had begun earlier with demonetisation and the implementation of GST causing money to shift away from gold and real estate and into mutual funds which have seen record inflows in recent years. The amount of money flowing into equities through Systematic Investment Plans (SIP) has surged in recent years, pointing to the growing awareness about mutual funds. Average inflows into systematic investment plans (SIPs) more than doubled between 2016 and 2020, going up from Rs.3,500 crore to Rs.8,100 crore a month.

The good and the bad

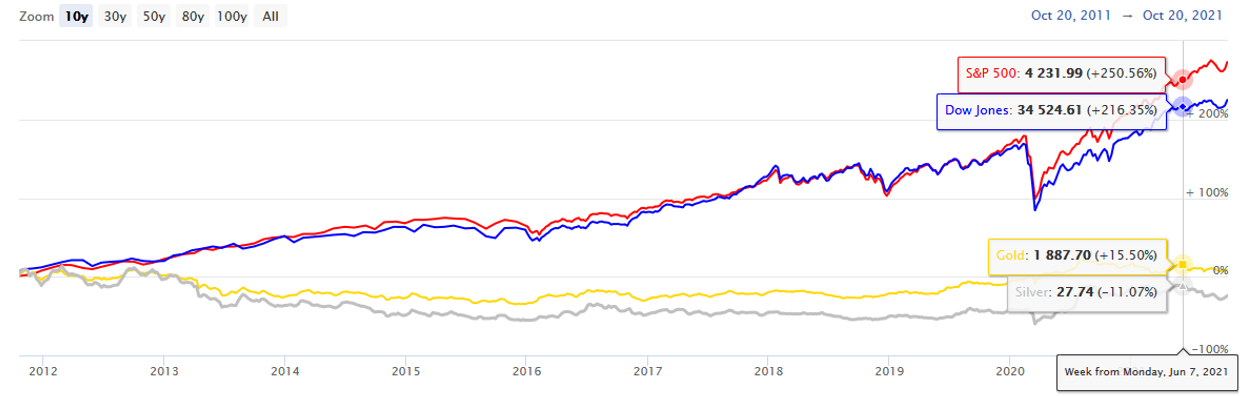

Objectively speaking, the rise of retail investors in the stock market is a positive development. The historical trend across countries shows that stock markets deliver the greatest returns compared to other assets like bank deposits or gold. With greater retail participation, more common people stand to benefit from the greater gains delivered by the stock market. In a way, it’s about democratising the markets and making it less of an elite phenomenon. Over the past decade, the Nifty50 Total Return Index or TRI has compounded at 11 per cent per annum and created $1 trillion of wealth. The stock market has therefore become a potent source of sustainable wealth creation in India. It stands to reason that if the wealth created by the stock market spreads more equitably across all classes, it will give free-market reforms a greater degree of acceptance and legitimacy than has been the case so far.

Furthermore, in a country where a mere 5 per cent of household wealth is held in the form of financial assets, stock market investments can drive the financialization of savings and wealth. That benefits the macro-economy as financial savings contribute much more to economic activity than savings in real assets like gold or real estate. When savings flow into financial assets be it bank deposits, government and corporate bonds, mutual funds, or direct investments in the equity market, the funds remain within the banking system and available for economic activity.

On the negative side, investments in stock markets carry a higher degree of risk which the common investor may not appreciate, particularly the younger investors who may not have experienced economic downturns or the cyclical ups and downs of the market. Such investors may not be able handle the down-cycles and are more likely to exit the market during downturns after incurring steep losses. However, seasoned investors understand that downturns are frequent occurrences in the stock market to be taken in stride and not a trigger for panic selling.

Retail investors are also more likely to follow the momentum of the market, which means they end up buying when the market is peaking. In this case too, the investor ends up making little or no money from his investments. In this context, retail investor behaviour is often characterised by two significant biases termed the ‘disposition effect’ and ‘overconfidence effect’. The ‘disposition effect’ is the tendency of investors to sell assets in which they have registered gains while continuing to hold assets in which they are making losses in the hope that they would register profits in time. This is reinforced by the ‘overconfidence effect’ which is the tendency to recognise gains and feel elated about successful trades, while ignoring losses and continuing to hold on to a loss-making stock in the expectation of a turnaround.

Also, the recent behaviour of retail investors in the US stock markets suggests that retail investors are more prone to chasing momentum. They seem to be at a greater risk of investing in high-priced stocks whose prices may have entered bubble territory. In fact, there is empirical evidence to show that individual investors who pick their own stocks for investment would earn poorer long-run returns in aggregate and are therefore better off investing in a low-cost index fund. This poor performance becomes more apparent when we include transaction costs such as commissions, bid–ask spreads, market impact, and transaction taxes. However, while transaction costs undermine returns, a more relevant consideration is the poor security selection ability of the average individual investor. Therefore, it is important to strengthen investor education with a focus on sensible investment practices that ensure returns in the long run.

Published in Unique Times Magazine, November 2021

(V.P. Nandakumar is the MD & CEO of Manappuram Finance Ltd. Views are personal.)