Up until the end of January 2018, stock markets around the world were scaling new heights and setting new records at regular intervals. In the US, the Dow Jones Industrial Average set a record when it closed at 26,616.71 on January 26, 2018. In India, the BSE Sensex set its own closing record at 36,283.25 on 29 January, 2018.

However, beginning in February, the picture has turned adverse for the markets. In just two weeks, the Dow Jones industrials posted a steep fall of 3200 points or 12 percent down from the record highs reached a few days earlier on 26 January. Indeed, February 5 was called the scariest day on Wall Street in years with stocks literally in free fall and, at one point, the Dow was down by almost 1,600 points, the biggest ever point decline during a trading day in history. The second half of February saw good recovery with stocks regaining bounce and recovering three-quarters of those losses. But then, there was more volatility to come. The Dow lost 680 points in the final two days of the month leaving it about 1,600 points down from the record high in late January. This sharp correction was totally unexpected because it followed an extended period of extremely low volatility and against the backdrop of a strong US economy.

The fall began with worries about rising inflation and the spike in US bond yields after data indicated tighter US jobs market. There was a fear that the stock markets had risen too high and too fast in recent months, and therefore a correction was both imminent and overdue. But then, the fact that it happened without any apparent trigger drew attention to a phenomenon that first appeared in the mid-seventies but which started gaining ground rapidly in the bullish period following the great financial crisis of 2008. Today, it has grown to such gigantic proportions that it threatens to become a new fault line in the financial markets. It is the rise of passive investing and the increasing importance of asset management funds that rely on a passive management or passive investing strategy.

What is passive investing?

Let’s begin by considering what the opposite, active investing, is about. Active funds management gives importance to the underlying fundamentals of a company in arriving at the investment potential of a particular security. Fund managers spend time and resources studying financial and valuation metrics before deciding to put money into it or recommending it to their clients and other investors. The larger purpose behind this diligence is to beat the returns generated by the broader equity markets. Unfortunately, this goal has been largely elusive during the current decade characterised as it was by a steady rise in stock prices to reach the record highs of January 2018. Indeed, the rise of passive investing can be explained in part by the demonstrated failure of active fund managers to consistently beat the markets.

For instance, the S&P Indices Versus Active (SPIVA) funds scorecard for 2016 shows that more than 60 percent of actively managed stock funds underperformed their respective market benchmarks. Mid-cap and small-cap funds were especially poor, having been beaten by the market on 89.3 percent and 85.5 percent of occasions respectively. Consequently, more and more analysts and investors saw active fund managers as being consistent underperformers and not worthy of their management fees. The role of the active manager became more difficult to justify, even more so after the financial crisis when many alternative avenues for investment emerged that brought simplicity, convenience and affordability to the investor.

The passive investment strategy emerged as the alternative to active investment in that it largely ignores analyses of the fundamentals of individual securities, in favour of investing in funds consisting of a weighted basket of securities that mimic the broader underlying stock indices. Such strategies enable passive funds to replicate—and thus track—the performance of the broader index (for example, the S&P 500). It means that passive funds are not concerned with beating the market (unlike active funds) and instead aim to simply earn the market return assuming that the market is likely to rise over a sufficiently long period of time. Put simply, rather than exercise judgment about which stocks to buy, the passive fund manager will just buy the shares representing a particular index, so that the returns delivered are in sync with the chosen index. You will not get to beat the index, but you will also not underperform.

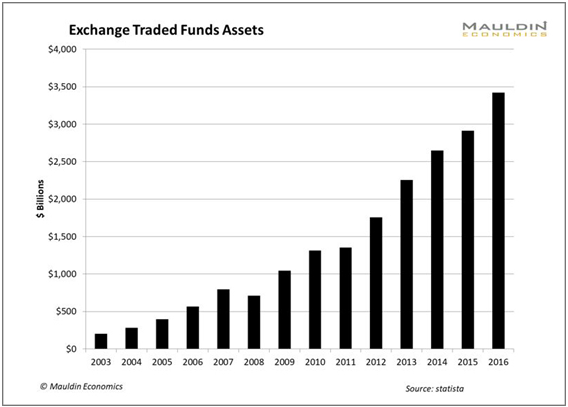

The important benefit for the investor is that passive fund management fees are usually a fraction of the fee charged by active funds. According to data of 2015, some index-tracking exchange-traded funds charge as little as $3 annually for every $10,000 they manage, while the average charged by U.S. stock mutual fund managers is $131. Moreover, these funds are easier to access and more convenient to trade, particularly the exchange-traded funds (ETF) that have mushroomed with the boom in passive investing in recent years. In fact, as of the beginning of 2017, there were almost 2,000 ETFs listed on exchanges in the United States alone, which managed a total of $2.56 trillion—20 percent more than they

The ETF market has experienced astounding growth over the last decade. There are now 5,000 ETFs traded globally with over $3.5 trillion in assets, a more than threefold increase since 2007.

Where comes the risk?

The problem with passive investing is that a market shock, as in the first week of February, would cause these strategies to sell into the weakness because this is the how they are programmed. With no room for the human element in this strategy, the decision to sell will be automatic when pre-set stop loss levels are triggered. In contrast, active or value investing will also have stop loss levels that get triggered when there is a fall, but at some point, the fund managers can exercise their judgement and resume buying, such as when they feel the selling has gone too far and valuations have become cheap. Likewise, when the share price of a particular company or sector increases, its value will increase relative to the market leading to greater allocation of funds from passive investing funds. This momentum based investment leads to winning stocks that keep on winning and the relative losers to keep on losing. Clearly, the passive strategy will work well for the investor when markets are on the rise but not so in a scenario of falling stock prices.

Over the past decade the US equity markets have seen strong growth in passive and systematic investment strategies that rely on momentum and volatility to decide how much risk to take. The evidence for this is seen in the huge increase in the AUM of mutual funds that are into blind index investing. In 2016, passive funds in the United States attracted $506 billion, while actively managed funds lost $341 billion in withdrawals. In fact, passive funds currently account for 29 percent of the U.S. market according to Moody‘s and are set to grab more than half the assets in the investment-management business by 2024 at the latest.

The shift from active to passive assets, and specifically the decline of active value investors, reduces the ability of the market to prevent and recover from sharp corrections. The approximately US$ 2 trillion that has shifted from active and value to passive and momentum strategies since the last financial crisis has effectively removed a large pool of money that would otherwise be on standby, ready to buy shares and securities on the cheap, and thus arrest a fall in prices before it gets to crisis levels.

Significantly, all these risks have come to the fore at a time of all-round valuation excesses. There is good reason to believe that most assets are at their high end of historical valuations consequent to the prolonged period of easy money policies followed by the US Fed and other central banks. Signs of these excesses can be seen everywhere, including multi-billion dollar valuations for tech startups and smartphone apps, and the sharp run up in the prices of bitcoin and other crypto- currency offerings with little or no intrinsic value.

Another related development of concern is that just as the stock markets appear headed for correction, the bond markets too are showing signs of weakness. Over the past two decades, most risk models have been relying on bonds to offset equity risk, and correctly too. However, now that US Federal Reserve has turned its back on easy money, this assumption is unlikely to hold true. From now on, when stock markets fall, don’t count on the bond markets to hold value. Indeed, one should not be surprised if stocks and bonds fall at the same time, a very unpleasant scenario for the market. In sum, the shift of investor funds towards passive or momentum investing, as opposed to active or value investing, has opened a new fault line that has the potential to tip over the markets into another crisis.

Published in Unique Times, April 2018

(V.P. Nandakumar is MD & CEO of Manappuram Finance Ltd.)