The US has an inflation problem

A jump in US inflation may pressure the Fed to tighten monetary policy sooner than expected. How would India fare in that scenario?

There is no doubt that the US economy is facing an inflation problem. And the risk is that if it is not handled with care, it can get out of hand.

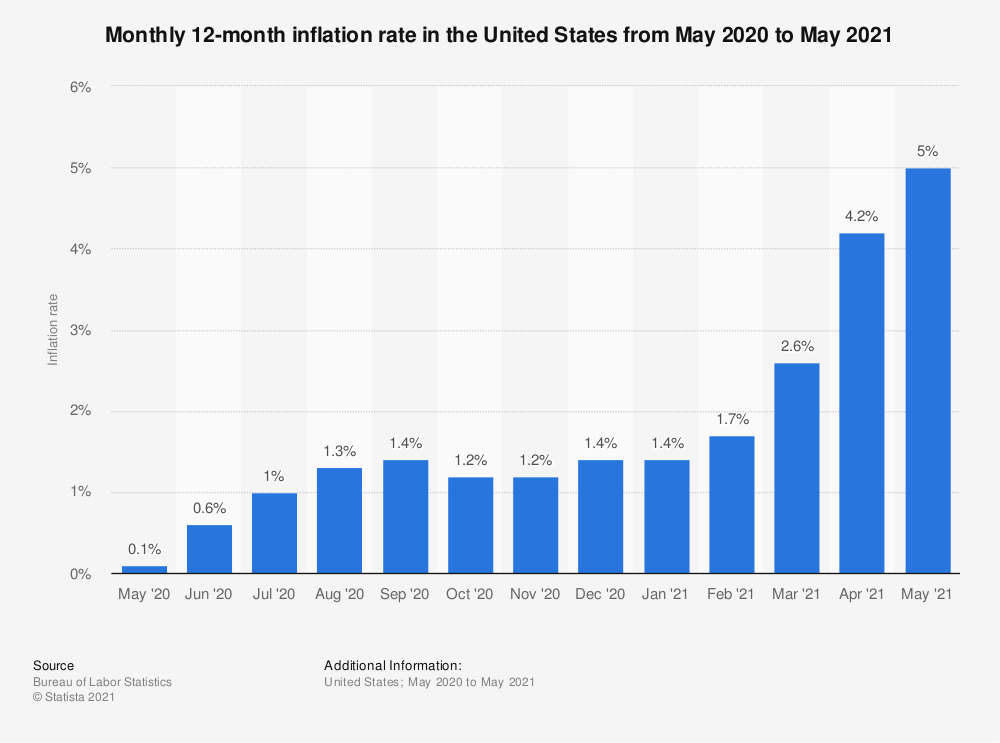

According to the US Labour Department, Consumer Price Index (CPI) in June 2021 increased by 5.4% from a year ago, the highest 12-month rate since August 2008. Earlier, the consumer price inflation for the month of May showed a 5% increase over the year, which was also the highest 12-month rate since August 2008. But the run-up in inflation had begun in April this year when consumer prices registered a 4.2% increase over the year. For the record, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) has long targeted an inflation rate of 2%, so these numbers are clearly well above their comfort zone.

Indeed, the US Fed has acknowledged that inflation is stronger and perhaps more durable than they had anticipated. When the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) met in June, they revised their estimated consumer inflation for the whole-year to 3.4%, which is 1 percentage point higher than their March projection, and double of what they had forecasted in June 2020. However, they insist there is no need to press the panic button as higher prices are transitory, and related to the peculiarities of an economy getting back on its feet after the unprecedented lockdowns.

It can be argued that comparing today’s price levels to those prevailing a year ago is subject to the base effect given that large parts of the economy were shut down last year. While that is true, the fact remains, inflation measured on a month-on-month basis also offers no comfort. US consumer price inflation jumped 0.9% month-on-month in June after recording a 0.6% gain in May that in turn followed a 0.8% increase in April and 0.6% in March. The strong run-up of month on month (MoM) readings over the past few months makes the Fed stance of inflation being ‘transitory’ open to question, if not outright doubt.

Predictably, these numbers have led to increasing calls for a faster winding down of the massive monetary stimulus the Fed has been injecting into the economy. It may be recalled that in March 2020, in response to the economic shock of the pandemic, the Fed had cut its benchmark federal funds rate sharply. The target for this rate (that banks pay to borrow from each other overnight) was brought down to near zero, to a range of 0% to 0.25%. Further, from June 2020 onwards, the Fed started buying US treasuries worth $80 billion and mortgage-backed securities worth $40 billion every month (a monthly injection of liquidity worth $120 billion) which continues to this day.

The rising prices point to strong consumer demand boosted by the good progress in vaccinations, the easing of restrictions on business as the virus recedes, the trillions of dollars in federal pandemic relief, and ample household savings that have surged in recent months (after liberal handouts from the federal government). Housing and shelter prices in US continue to increase at a frantic pace, strengthening the belief that inflation could be sticky. Housing costs have an undue bearing on inflation risks as primary rents and owners’ equivalent rent account for a third of the CPI basket.

The current increase in inflation has other structural causes that are not entirely related to the pandemic. Driven by all the stimulus money, the economy is growing at a fast pace, and demand is outpacing supply as the production capacity of the economy limps back to normal after the pandemic shock. Wages have risen significantly against a scenario of firms reporting acute difficulties in hiring suitable labour to operate their businesses. For instance, in May this year it was reported that more than nine million Americans wanted jobs but were unable to find them while at the same time companies reported they had more than nine million unfilled job vacancies, a record high. This explains why wages have risen even as the unemployment rate which stood at 5.9% in June continues to be above the pre-pandemic rate of 3.5%. This dichotomy has come about because of overly generous unemployment benefits which have made labour choosier about the jobs they accept. However, the current series of benefits are set to expire in September 2021, and labour shortages and the pressure on wages should ease somewhat, even though wage increases are known to be sticky.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008

It is a fact that US monetary policy has been on an expansionary path ever since the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008. GFC was a watershed in the economic history of the world, because of the resort to unconventional methods by the central banks of the advanced economies. The idea of quantitative easing (QE) emerged that to restore growth and employment, central banks should stimulate the economy by injecting as much money as needed and cutting interest rates sharply. At the start of the meltdown in 2008, the US Federal Reserve held assets worth about US$870 billion. By 2015, with successive rounds of QE, it had ballooned to US$ 4.5 trillion. Many predicted inflation but it did not happen. However, asset prices (stocks, bonds, commodities, and real estate) did go up sharply along with equities in emerging markets including India. In 2018, the Fed decided to normalise its monetary policy and began by targeting a US$ 10 billion monthly reduction of its bond holdings that would gradually increase to US$ 50 billion. Within a year, the Fed had succeeded in bringing down its balance sheet size to US$ 3.8 trillion. But in the aftermath of the pandemic, the US Fed restarted bond buying and today its assets have shot up to over US$ 8 trillion. All of this has a direct bearing on the supply of money in the economy and gives strength to fears of inflation. Against this backdrop, the US government’s $1.9 trillion Covid relief bill signed into law by President Biden in March will put more money into the hands of people without necessarily adding to output.

Likely consequences of higher US inflation

Should higher US inflation be here to stay, what would be the international consequences? In other words, what would be the consequences if the Fed is forced to tighten monetary policy well ahead of schedule? Afterall, it would be sensible for policymakers around the world, and particularly of the vulnerable economies, to be prepared for the possibility of US interest rates rising sooner and faster than currently predicted.

History tells us that if US interest rates were to rise sharply, countries with large foreign-currency debt (particularly short-term debt maturing within a year) and holding relatively low foreign-exchange reserves would become vulnerable to a currency and debt crisis. In this context, the experience of 2013 is quite relevant. That was when the US Fed made a serious attempt to raise interest rates, in what later came to be known as the “taper tantrum.” The world had come out of the global financial crisis, and the Fed decided to reduce, or taper off, the quantitative easing begun in 2008. Essentially, this meant reducing the purchases of treasury bonds and thereby the quantity of money being pumped into the economy. However, by this time investors had come to depend on Fed support for sustaining asset prices, and they responded to the prospect of decline in bond prices by hitting the sell button in panic.

The result was that bond prices fell, and yields shot up. The consequences were felt all over the world as investors pulled their money back to the safety of the US dollar, leading to sharp outflows from emerging markets (including India) which forced central banks to hike interest rates. As foreign portfolio investors began to pull their money out of India, the rupee fell by over 15 percent between late-May and late-August 2013. India found an unwelcome mention on Morgan Stanley’s “fragile five” list along with Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey. The Reserve Bank of India was forced to raise interest rates to cap the outflow. However, success was limited and eventually India had to borrow about US$ 30 billion at a high cost under the FCNRB route to restore stability.

How vulnerable is India today?

Can something like that happen again? The chances are unlikely because as against $275 billion in forex reserves in August 2013, India’s forex reserves currently stand at over $600 billion. Hence, there is greater confidence among policymakers today that the economy can deal with a taper tantrum like situation should it arise. However, that does not rule out short-term volatility and pain.

As interest rates rise in the US and other advanced economies, there will be an initial period when emerging market economies will see capital stampeding back to the US attracted by the higher interest rates. Almost certainly, there will be turbulence in the capital and currency markets with falling stock prices and the rupee shedding value. To counter the outflow, the RBI would have to raise interest rates besides drawing down on its accumulated forex reserves to support the rupee. A weakened rupee can have an inflationary impact as cost of essential imports especially petroleum goes up. Further, higher interest rates also add to overall inflation by pushing up the cost of business. The turbulence will gradually wind down once the rupee is stabilized and international investors come to realize that potential returns from investments in India outweigh what is on offer in the advanced economies.

One of the bright spots for the Indian economy in the gloom of the pandemic age has been corporate India’s remarkable success in cost cutting which has led to earnings beating estimates. In recent years, India has made great strides with its Digital India campaign, having emerged as the second-fastest digital adopter among seventeen major digital economies. The digital infrastructure has added to the resilience of India’s corporate sector and it was a key enabler for cost cutting during the pandemic. Besides, start-ups in India’s tech-enabled services sector have become a magnet for foreign investors. The potential for growth here is enormous and unlikely to be missed by international investors.

The other good news is that after the introduction of the GST in 2017, we appear to have overcome all the teething problems and stabilized the system. Over the last 10 months, GST collections have consistently exceeded the Rs.100,000 crore level barring collections pertaining to June 2021 which was affected by the second wave. India has now become one common market for most goods and services and that has given a boost to e-commerce. GST has also served to accelerate the formalization of the Indian economy which has helped the organized sector increase its market share and reap economies of scale. That is one reason why in the recent earnings seasons, most companies have beaten estimates and why the economy has rebounded so well, both after the first and the second waves. Moreover, India’s infrastructure has undergone major upgradation, and our roadways and railways are in much better shape now. In the coming years, major gains will accrue from this improvement by way of lower costs for business which in turn improves export competitiveness. Recently, it was announced that India had exported goods worth a record $35.2 billion in July 2021 while exports in Q1FY22 stood at a record $95 billion. Importantly, India’s merchandise exports in July 2021 represented a significant increase of 34% over what was achieved July 2019, before the pandemic.

The taper tantrum of 2013 was an unhappy experience for India and one reason was that the economy was already overheated then. That was because the government had delayed rolling back the generous fiscal stimulus provided after the 2008 global crisis setting off prolonged high inflation. In contrast, in the current crisis, India has been something of an outlier in terms of its fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic which has been faulted for inadequacy. However, this may well turn out to be the right response given the storm clouds gathering ahead.

Summing up, the global economy would face significant headwinds if US inflation gets out of hand. As for India, barring an initial period of turbulence, we are likely to emerge stronger and better off. The Indian economy has entered a virtuous cycle where digital and physical infrastructure combine with structural reforms of recent years to improve efficiency and bring down costs all around. We will continue to remain attractive for foreign investment.

Yes, there will be a taper ahead, but no tantrum.

Published in Unique Times Magazine, August 2021

(V.P. Nandakumar is MD & CEO of Manappuram Finance Ltd. Views are personal.)