By V.P. Nandakumar

The US consumer price index rose 6.8% in November 2021 year on year, the fastest pace of increase since 1982, and the sixth straight month in which inflation topped 5%. Regular readers of this magazine may recall that in the August 2021 issue, my article titled “The US has an inflation problem” had dealt extensively with the subject of rising inflation in the US following the pandemic. In the five or six months since, the problem has become even more acute. In December 2021, responding to the high inflation, the US Federal Reserve announced a faster taper of its bond buying programme which has been injecting $120 billion of liquidity every month since June 2020. Bond purchases will now be reduced by $30 billion each month, which will end all fresh bond purchases by March 2022. The accelerated timetable puts the Fed on course to start raising interest rates in the first half of 2022.

Here in India, inflation as measured by the wholesale price index (a proxy for producer prices) accelerated to 14.23% in November 2021, the highest since April 2005, due to a sharp increase in manufacturing costs and food prices. This has given rise to renewed concerns that rising inflationary pressures will soon have to be countered by the RBI raising interest rates. The gap between retail and wholesale price-based inflation has widened in recent months as many companies struggle to absorb surging input costs that undermine their profitability. Wholesale inflation has remained in double-digits for eight months in a row now while retail inflation continues to hover around 5%. It may just be a matter of time before the high WPI inflation spreads to consumer prices as well.

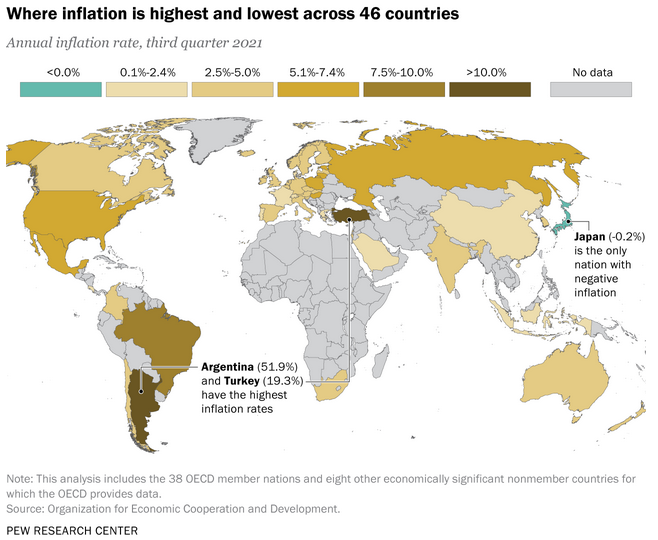

A look around the world

The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization has said food prices globally are now at their highest levels in more than a decade. According to the International Monetary Fund, consumer prices could rise about 4.8% globally in the next year. As the world braces for higher inflation everywhere, here is a look at how the leading economies of the world are faring.

China's consumer price index rose 2.3% year on year in November 2021 while the producer price index went up 12.9%. An ongoing crunch in energy supplies was the major contributor to the rise in producer price inflation as the cost of coal, a leading source of energy in the country, has risen sharply. The world's second largest economy is growing at the slowest pace in a year as the energy shortages, shipping disruptions, and a deepening real estate crisis take their toll. China’s rising inflation has the world worried considering China's place in the global supply chain and its role as the world's factory supplying a staggering range of goods to consumers around the world.

In the U.K., inflation climbed to a 10-year high with CPI rising by 5.1% year on year in November, which was more than double the central bank’s target. The UK’s Office for National Statistics attributed the rise in inflation to the prices of petrol and second-hand cars, but prices have risen for almost all goods and services suggesting that price pressures are being felt across the economy. As inflation surged, the Bank of England hiked interest rates for the first time since the onset of the pandemic, increasing its main interest rate to 0.25% from its historic low of 0.1%.

In Germany, inflation continued to rise going up from 4.5% in October to 5.2% in November (the highest rate registered in the country since June 1992) driven by the base effect of low prices that prevailed for much of 2020. The sharp fall in petroleum prices in 2020 along with a temporary reduction of value-added tax (VAT) had lowered prices during the year. Later, the introduction of a CO2 pricing in the transport and housing sectors at the beginning of 2021 (a charge of 25 euros, equivalent to US$ 28, per tonne of carbon dioxide emitted) and sharply higher energy prices (up 22.1 per cent year-on-year in November) added to the inflationary pressures.

In France, inflation rose unexpectedly in November to hit its highest level in 13 years, according to a preliminary estimate. Consumer prices rose 0.4% from the previous month, amounting to an annualised inflation rate of 3.4%, the highest since September 2008. In line with the worldwide trend, the November increase was mostly driven by surging energy prices, which were up 21.6% over the last one year.

While inflation surges around the world, Japan continues to be a notable exception. Although Japanese policymakers have long sought to stimulate the economy by increasing inflation and thereby shake it out of its long-term deflationary trend, consumer prices have not moved. It appears that after decades of very low inflation, Japanese shoppers tend to resist the idea of paying higher prices and businesses have refrained from raising prices. Consequently, companies tend to hoard cash and go slow on investments, while keeping the labour market rigid so that workers don’t get to change jobs easily or get pay increases. In October, Japan’s consumer prices increased by just 0.1% from a year earlier, while core inflation (which excludes volatile food and energy prices) actually fell by 0.7%. Interestingly, most of the inflationary forces hitting other countries, such as higher prices for oil, commodities, and microchips also apply to Japan. The difference lies in the way companies and consumers react. Japan has an aging and shrinking population that encourages people to be cautious with their spending leading to a chronic shortfall in consumer demand.

Causes of current inflation

Why has inflation risen so quickly? The answer to this question holds the key to an understanding of how long the surge can be expected to last and what policymakers should do about it. Many economists believe that the recent bout of inflation is different from other inflationary periods that were linked to the regular business cycle. Among their explanations include the continuing disruptions in global supply chains after the pandemic, the unsettled labour markets, the base effect from measuring prices against the low levels that prevailed last year after COVID-19 had shut down parts of the economy, and the strong rebound in consumer demand after local economies were reopened.

Supply chain issues: If inflation today has become something of a global phenomenon, the havoc wreaked by the pandemic on global supply chains gets a fair share of the blame. By constricting supplies of a range of goods at a time when pent-up demand is looking for an outlet, it has set the spark to inflation on a global level. In hindsight, it is no surprise that a globalized economy where manufacturing is dispersed across multiple locations often in different countries (and therefore dependent on smooth and efficient logistics to keep going) can come to a freeze when struck by a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic. Covid-19 squeezed supply chains, restricted international and local travel, and shut down businesses and services. Now, even as the world is recovering from these shocks, new variants of Covid-19 continue to pose a threat.

Shipping costs: The Global shipping crisis—as seen in the severe shortage of containers and ships having to wait for long to dock at ports—is likely to go on delaying goods traffic and stoking inflation by increasing the cost of logistics. Shipping has rarely been a subject to attract the attention of economists who have always paid more attention to raw material and labour costs as compared to transportation. But those days may be over. The cost of shipping a 40-foot container (FEU) unit used to be about $1,300 before the pandemic. It surged to a record high of over $11,000 in September 2021 but has now come down by about 15% according to the Freightos FBX index. With 90% of the world's merchandise being shipped by sea, soaring shipping costs are exacerbating global inflation.

Petroleum prices: Energy prices are rising around the world with the economic recovery and people returning to the offices. Europe is struggling to secure enough gas and coal with the onset of winter. Soaring gas and oil prices hurt consumption and aggravate inflation. The gas market is going through a turbulent phase which has driven prices in Europe higher by 280% this year while comparable US prices have doubled. The spike is being attributed to a range of factors from low storage levels to reduced Russian supplies and lower investments in hydrocarbons. Also at fault is the aggressive implementation of green energy policies that deter investments in the hydrocarbon sector. A side effect of surging gas prices is higher food costs as the production of fertiliser uses gas as a feedstock.

Commodity prices: The spike in the prices of commodities, especially steel, aluminium and metals like copper and zinc, has cast a shadow over the recovery and added to the inflationary pressures. The profit margins for manufacturers shrink when raw material costs go up. Households are paying more for gas, groceries and eating out, which constricts their ability to spend elsewhere. Surging commodity prices are an early warning of future inflation as commodity markets react more quickly to changes in economic conditions than prices for final goods.

Shortage of semiconductors: The worldwide shortage in the supply of semiconductors has affected manufacturing and is yet another reason for the upward pressure on consumer prices. In the modern world, semiconductors are at the heart of products ranging from computers and phones to our vehicles and appliances. Orders for everything from cars to televisions to touch-screen computers and the like are being held back for six months and more merely for want of adequate chips. With production of new cars impacted by the semiconductor shortage (modern cars make use of a lot of electronics), manufacturers have pushed up prices which has spilled over into the used car market. As the supply of semiconductors increases, we may expect some easing of inflation on this count, but the process is likely to be drawn out.

Fiscal and monetary stimulus: This is the elephant in the room that most policymakers would prefer not to see. The massive amounts of liquidity injected into the global economy through fiscal and monetary stimulus by central banks around the world to lend support to the economic recovery has had some unintended consequences too. As the famous definition goes, inflation is too much money chasing too few goods and services. Approximately US$10.8 trillion was injected into the world economy by way of fiscal stimulus and this is equivalent to 10% of global GDP. With so much extra money finding its way into the economy in a short period, high inflation was perhaps a foregone conclusion.

Consequences and likely outcomes

The tapering of bond purchases by the US Fed followed by a faster lift-off of interest rates will put pressure on stock prices in the US as well as emerging markets where the risk off mode will lead to foreign portfolio investments (FPIs) flowing out. In fact, FPIs have pulled out Rs.29,702 crore from the Indian equity and debt markets in December 2021 which saw the announcement of faster tapering by the US Fed as well as uncertainty over the Omicron variant. Gold prices will likely be under pressure initially as reduced stimulus and interest rate hikes by central banks tend to push government bond yields up, raising the opportunity cost of holding bullion which yields no interest. However, there is no certainty that US inflation can be brought under control without raising interest rates to the point where the economy tips over into a recession, and that means there’s a lot more fight left in gold.

Back in 2017 and 2018, the US Fed had raised interest rates seven times in a row but when growth slowed, they changed course and cut interest rates again. At the time, inflation was low and that gave the Fed the room to revert to lower interest rates. However, this time around, inflation is at a four-decade high and if the Fed were to reverse course without fully wringing out inflation, the pressures can mount leading to stagflation. And should inflation remain stubborn, gold prices will likely bounce back as the metal has historically done well under high inflation.

In India, the RBI will be under pressure to hike interest rates to curb inflation. This will put pressure on the financial services sector which typically does better under a low interest rate regime. For now, the RBI has been patient with measures to support growth. Once growth recovers, the focus will shift to inflation. With domestic inflation risks on the upside, and with global interest rates also going up, interest rates in India are set to increase. A rising interest rate cycle is a challenge for bond market investors especially those investing in longer maturity bonds as capital losses are higher for longer holding periods as compared to shorter duration bonds.

As for the equity markets, they have perhaps delivered their due ahead of time considering the record gains since the lows of the pandemic. A period of consolidation is more likely than a repetition of the outperformance of the last two years. However, given the unpredictability of the markets, it would also be wise to pray for an uneventful year without any more of black swan events to throw all our calculations out of gear.

Published in Unique Times Magazine, January 2022

(V.P. Nandakumar is MD & CEO of Manappuram Finance Ltd. Views are personal.)